The recent decision by the Travis County District Court ruling that policy changes such as the land development code rewrite are subject to zoning petition protests by homeowners is disappointing. Unless overturned, the ruling effectively requires a super-majority of City Council members to pass many of the meaningful reforms that are desperately needed in Austin and in all Texas cities.

While we’re optimistic that the decision will be both appealed and overturned, we’re also confident that regardless of temporary setbacks such as this both the land development code rewrite and other ways to increase our desperately limited housing supply will be found and implemented.

Furthermore, we are confident that an even greater majority of people vote for truly progressive elected officials, at every level of government and in every branch, who understand how urgent and necessary these changes are.

Furthermore, we believe that the City Council could today pass some important measures. Several are detailed below. As these measures only reference the text of the land development code and not the zoning, they could be passed in spite of the ruling.

We look forward to working with the city and all those in favor of progress to rebound from this temporary setback and create an Austin that is truly for everyone and not just the few.

Proposed Changes

1) Preservation Bonus

Implement House Scale Preservation on residential properties (SF-1, SF-2, SF-3) as defined in exhibit 1

Implement Multi-Unit Preservation Incentive for multifamily properties (all zones more intensive than SF-3) as defined in exhibit 2

2) Compatibility

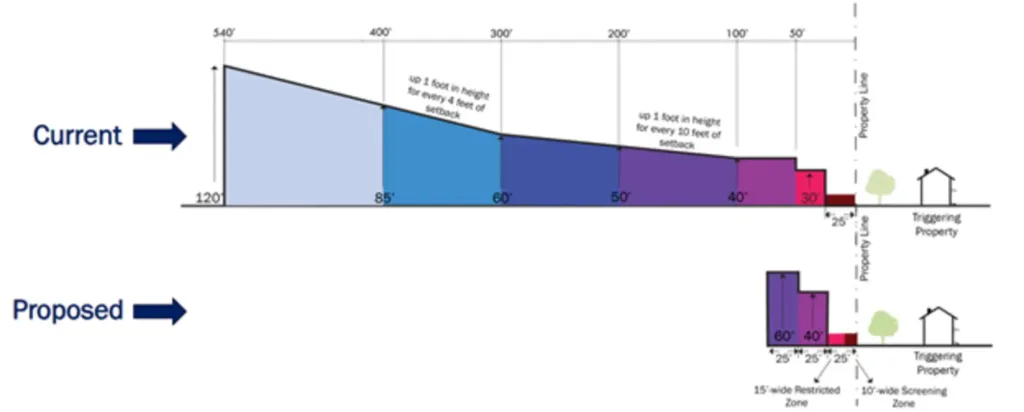

Compatibility is triggered by zoning but not current use.

Compatibility Height Setback Distance from the lot line of the triggering property:

* Less than 50 feet = Overall height shall not exceed 35 feet

* Between 50 and 100 feet = Overall height shall not exceed 45 feet

* Over 100 feet = Overall height set by zone standards

3) Setback changes

For all residential and multifamily zones:

* Reduce rear setback from 10 feet to 5 feet.

* Reduce side street setback from 15 feet to 10 feet.

4) ADU changes

Eliminate parking requirements for ADUs.

Allow ADU’s city wide on any residential or multifamily lot including SF-2.

5) Minimum lot size and width:

* For all zones with a minimum lot size that is greater than 5,000 sf shall be reduced to 5,000 sf * For all zones with a minimum lot width that is greater than 45 feet shall be reduced to 45 feet

Exhibit 1)

(A) Purpose and Applicability.

(1) By providing development incentives for maintaining certain existing structures, this section encourages preservation of the City’s older housing stock while increasing opportunities for new housing.

(2) This section applies to all residential development on sites within a Residential House- Scale Zone.

(B) Administration and Enforcement.

(1) To request a development incentive under this section, an applicant must submit a request on a form provided by the director concurrent with a development application. The request must include information required by the director to determine whether the proposed development and the existing structure sought to be preserved comply with all applicable requirements.

(2) The director may establish requirements for administering and enforcing this section, including procedures for:

(a) Determining whether an existing structure meets the requirements for preservation under Subsection (D)(1); and

(b) Monitoring compliance with limitations on altering or expanding a preserved structure under Subsection (D)(2).

(C) Preservation Incentives.

(1) If the director approves a request to preserve an existing structure under Subsection (D), the following incentives apply to development located on the same site as the preserved structure:

(a) Development may exceed the maximum number of units allowed on a site in the base zone by one unit;

(b) The preserved structure does not count towards the maximum floor area allowed for a site in the base zone;

(c) Additional units are not subject to minimum parking requirements; and

(d) Within the Residential-2A (R2A), Residential-2B (R2B), and Residential-3 (R3) zones, development may not exceed a maximum impervious cover of:

(i) 45 percent, if the site contains two units;

(ii) 50 percent, if the site contains three units; and

(iii) 55 percent, if the site contains four units.

(2) Except as provided in Subsection (C)(1), development approved under this section must comply with all applicable requirements of this Title.

(D) Preservation Requirements. The preservation incentive established under Subsection (C) applies to proposed development only if the director determines that all applicable requirements of this subsection are met.

(1) Eligibility Requirements. The director shall approve a request to apply the preservation incentive established under Subsection (C) if:

(a) For at least 30 years, the structure has existed as the principal use on the site and has remained in the same location;

(b) All of the existing structures on the site of the proposed development were constructed in compliance with City Code; and

(c) The site complies with all applicable requirements of this Title, including Article 23-2H (Nonconformity); and

(d) The proposed development for which the incentive is sought will increase density on the site by at least one dwelling unit.

(2) Alterations to Original Structure. The preserved structure may not be modified or altered except as follows:

(a) Expansion of Structure. The preserved structure may not be modified or altered to exceed the maximum floor-to-area ratio allowed for the use in the applicable base zone.

(b) Wall Demolition and Removal.

(i) Except as provided in Paragraph (iii), no more than 50 percent of exterior walls and supporting structural elements, including load bearing masonry walls, and in wood construction, studs, sole plate, and top plate, of an existing structure may be demolished or removed. For purposes of this requirement, exterior walls and supporting structural elements are measured in linear feet and do not include interior or exterior finishes.

(ii) The exterior wall of the preserved structure must be retained, except that a private frontage, per Section 23-3D-5 (Private Frontages), may be added to a preserved structure that does not have a private frontage.

(iii) Structural elements, including framing, may be replaced or repaired if necessary to meet health and safety standards. A repair or replacement

Exhibit 2)

of a structural element is necessary to meet minimum health and safety standards when the repair or replacement is required by the building official, the code official, the Building and Standards Commission, or a court of competent jurisdiction.

(c) Roof Alterations.

(i) If the structure has a side-gabled, cross-gabled, hipped, or pyramidal roof form, the addition must be set behind the existing roof’s ridgeline or peak.

(ii) If the structure has a front-gabled, flat, or shed roof form, the addition must be set back from the front wall one-half of the width of the front wall.

(iii) Retention of the original roof configuration and pitch up to the greater of:

• 15′ feet from the front façade; or

• The ridgeline of the original roof.

(d) Alteration or Replacement of Foundation. Replacement or alteration of an original foundation may not change the finished floor elevation by more than one foot vertically, in either direction.

(e) Relocation Prohibited. A preserved structure may not be relocated.

(A) Purpose and Applicability.

(1) By providing development incentives for maintaining certain existing structures, this section encourages preservation of older housing stock while increasing opportunities for new housing.

(2) This section applies to all residential development on sites within a Residential Multi- Unit Zone.

(a) Exception.

This section does not apply to the Residential Multi-Unit 1 (RM1) Zone.

A property zoned RM1 that participates in the preservation incentive must comply with Section 23-3C-3060 (House-Scale Preservation Incentive).

(B) Administration and Enforcement.

(1) To request the development incentives established in this section, an applicant must submit a request on a form provided by the director concurrent with submittal of a development application. The request must include information required by the director to determine whether the proposed development and the existing structure sought to be preserved comply with all applicable requirements.

(2) The director may establish requirements for administering and enforcing this section, including procedures for:

(a) Determining whether an existing structure meets the requirements for preservation under Subsection (D)(1); and

(b) Monitoring compliance with limitations on altering or expanding a preserved structure under Subsection (D)(2).

(C) Preservation Incentives.

(1) If the director approves a request to preserve an existing structure under Subsection (D), the following incentives apply to development located on the same site as the preserved dwelling units:

(a) Development may exceed the maximum number of units allowed in the base zone by 50 percent; and

(b) The structures that contain the preserved dwelling units do not count towards the maximum site-level floor area allowed in the base zone.

(2) Except as provided in Subsection (C)(1), development approved under this section is subject to all applicable requirements of this Title.

(D) Preservation Requirements. The preservation incentives established under Subsection (C) apply to proposed development only if the director determines that all applicable requirements of this subsection are met.

(1) Eligibility Requirements. The director shall approve a request to apply the preservation incentives established under Subsection (C) if:

(a) For at least 30 years, the principle use of the site of the proposed development has been residential use;

(b) At least one or more of the existing structures on the site was constructed at least 30 years prior to the application date;

(c) The proposed development will retain a minimum of 75 percent of:

(i) The existing dwelling units; or

(ii) The dwelling units that existed on site five years preceding the application date; and

(d) All of the existing structures on the site of the proposed development were constructed in compliance with City Code;

(e) The site complies with all applicable requirements of this Title, including Article 23-2H (Nonconformity); and

(f) The proposed development that will receive the incentive will increase density on the site by at least 10 percent.

(2) Alterations to Original Structure. Each existing structure with preserved dwelling units may not be modified or altered except as follows:

(a) Expansion of Structure.

The structure may not be modified or altered to exceed the maximum floor-to-area ratio allowed for the use in the applicable base zone.

(b) Wall Demolition and Removal.

(i) Except as provided in Paragraph (iii), no more than 50 percent of exterior walls and supporting structural elements, including load bearing masonry walls, and in wood construction, studs, sole plate, and top plate, of an existing structure may be demolished or removed. For purposes of this requirement, exterior walls and supporting structural elements are measured in linear feet and do not include interior or exterior finishes.

(ii) The front exterior wall of each existing structure that faces the primary street must be retained, except that a private frontage may be added to a existing structure that does not have a private frontage.

(iii) Structural elements, including framing, may be replaced or repaired if necessary to meet minimum health and safety standards. A repair or replacement of a structural element is necessary to meet minimum health and safety standards when the repair or replacement is required by the building official, the code official, the Building and Standards Commission, or a court of competent jurisdiction.

(c) Roof Alterations.

(i) Retention of the original roof configuration and pitch up to the greater of:

• 15′ feet from the front façade; or

• The ridgeline of the original roof.

(d) Alteration or Replacement of Foundation. Replacement or alteration of an original foundation may not change the finished floor elevation by more than one foot vertically, in either direction.

(e) Relocation Prohibited. A preserved structure may not be relocated.